Soft-body Armor Analysis and Design for Law Enforcement

- Glossary

- The needs for Soft-body Armor

- Law Enforcement Armor Specs

- Material Specifications

- Aramid Fiber Composition

- Defects & Strengthening Mechanism

- Manufacturing Process

- Disclaimer

Glossary

DOJ: United States Department of Justice.

NIJ Standard: From National Institute of Justice (DOJ). The only nationally accepted standard for the body armor worn by law enforcement and corrections officers.

Kevlar®: Registered bullet-proof product form DuPont™.

Kinetic Energy: The work needed to accelerate a body of a given mass from rest to its stated velocity.

Ultimate Tensile Strength: The capacity of a material or structure to withstand loads tending to elongate.

Density: The volumetric mass density, of a material is its mass per unit volume.

Stiffness: The extent to which an object resists deformation in response to an applied force.

Young’s Modulus (aka. Tensile Modulus, or Modulus of Elasticity/ Elastic Modulus): Measurement of the ability of a material to withstand changes in length. Defined as the ratio of tensile stress to tensile strain.

Stress-Strain Curve: Uniquely defined and is found by the amount of deformation (strain) at distinct intervals of tensile or compressive loading (stress).

Elongation: The amount of strain it can experience before failure.

Thermal Conductivity: A measure of a material ability to conduct heat.

Crystallinity: The degree of structural order in a solid where atoms or molecules are arranged in a regular, periodic manner. It has a big influence on hardness, density, transparency and diffusion.

Liquid Crystalline: state of matter which has properties between those of conventional liquids and those of solid crystals. Indication of Short Range order (Little Repeating order) and Long Range order only in small volumes.

Anisotropy: The property of being directionally dependent, which implies different properties in different directions.

Point Defect: Where an atom is missing or is in an irregular place in the lattice structure. Includes: self-interstitial atoms, interstitial impurity atoms, substitutional atoms and vacancies.

Thermosetting Polymer: A polymer that is irreversibly hardened by curing from a soft solid or viscous liquid prepolymer or resin.

W/m-K: Thermal Conductance, Watts per meter-Kelvin.

GPa, MPa: Giga, Mega Pascal.

psi: The pressure resulting from a force of one pound-force applied to an area of one square inch. In SI units, 1 psi is approximately equal to .

The needs for Soft-body Armor

Nowadays, protection clothes are widely used not only for army but also for civilians and it has significantly contributed to the safety of human. In military, protection clothes, or also called bullet-proof vest is used for soldier which can reduces the force of a bullet in order to minimize the damage a ballistic projectile can cause. Thanks to protection clothes, our lives have advanced in many positive ways.

This research aims to analyze the commercial use of aramid fiber (trademark name is Kevlar®) in ballistic-propellant armor specifically designed for Law Enforcement Officer who have to face potential confrontation threats with firearm on a daily basic.

Law Enforcement Armor Specs

In order to prevent casualties because of high velocity ammunition and increase the movement ability for law enforcement officers, a lightweight ballistic-propellant material has been the main focus of manufacturers. The determinants can be listed solely in these categories:

- High tensile strength to resists impact

Energy absorption capacity and impact load resistance are primarily the main concerns when dealing with ballistic resistant clothes. A ballistic-propellant armor should be able to resist the kinetic energy of a relatively low impact bullet (velocity < 600𝑚/𝑠) 1 2 as well as its fragmentation which is Type II based on the NIJ Standard of the US Department of Justice for ballistic resistance of body armor 3.

- Low density to decrease total body weight and maximize the mobility

Law enforcement officers in pursuing criminals typically on foot which requires the material to have low density in order to cut down the total carrying masses or saving up for another layer to enhance the resistances.

- High Young’s Modulus to prevent damages

High Young’s modulus is an extreme factor for energy absorption feature because it indicates the capability of material to deform elastically before permanently broken and since the vest covering within millimeters around the body, the modulus should be large to maximize the impact resistance through stacked layers.

- High Extensibility

Similarly, the elongation at break should be high to maximize the ability of each layer to dissipate the penetrating energy because energy absorption will cause plastic deformation (also permanent) until failure.

- Low thermal conductivity to resists exothermic related impacts

The material should have low thermal conductivity in order to marginalize the explosion impacts since law enforcement officers have constantly facing fire related hostility such as dealing with explosive firearms and especially fire hazardous situation.

- Other requirements

Telecommunications should not be interrupted which could affect the officers whose communication availability is vital.

Material Specifications

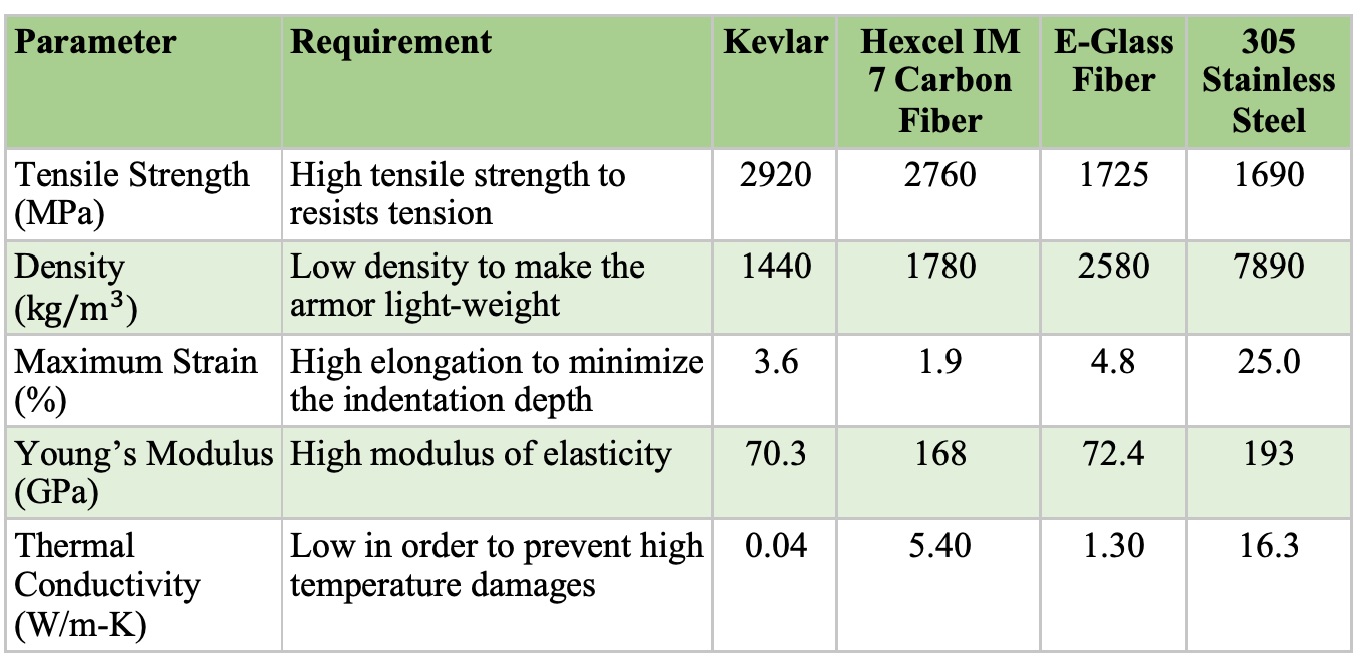

Table 1: Comparison between materials for soft body armor. Information is correctly cited at the article written time with multiple references 4 5 6 7

Table 1: Comparison between materials for soft body armor. Information is correctly cited at the article written time with multiple references 4 5 6 7

It can be seen that 305 Stainless Steel soon be ruled due to the massive density and thermal conductivity despite being highly ductile and stiffer the most. E-Glass fiber seemingly good at extensibility but outweighed amongst fiber and has the least tensile strength. Hexcel IM 7 Carbon Fiber and Kevlar Fiber are the two ideal materials left, having high modulus and low strain indicates the highly stiffness of Hexcel IM 7 Carbon whereas Kevlar still in the lead in term of strength to weight ratio.

Conclusively, Kevlar Fiber with the extraordinary strength to weight ratio, low density and relatively high strain as feature for lightweight and extensibility, superior thermal stability and comply with other requirements, is the selected material for further examination.

Kevlar Properties

Further examination of Kevlar Fiber properties indicate that

Mechanical Properties

- Tensile strength

The tensile strength of Kevlar as of 2920 MPa is highest amongst fabric materials whereas being the most light-weight material (Table 1).

- Extensibility

The maximum strain measured in Kevlar is 3.6% which is relatively high for fibers as compare to Hexcel IM 7 Carbon fiber and E-glass fiber.

- Young’s modulus

The low modulus of elasticity at 70.3GPa shows that Kevlar is easy to deform permanently compare to other fiber (Hexcel IM 7) but it also means that Kevlar has lower stiffness and more flexible (Table 1).

- Density

Kevlar is relatively low in comparison with other common fabric materials with 1440 kg/ which remarkably light-weight compared to 305 stainless steel whilst twice as strong (Table 1).

Thermal Properties

Thermal conductivity of Kevlar is impressively low in comparison with only 0.04 W/m-k which demonstrates the thermal stability of it. In the low-temperature range, aramid fibers retain their properties even at −70°C 8.

Other Properties

Kevlar has no metallic properties which cannot interfere with electronic devices 9. This is a dramatic improvement compared to other ballistic-propellant armor made of stainless steel or other metal alloys. Thus, prevent jamming or disconnection when communicate via radio receivers.

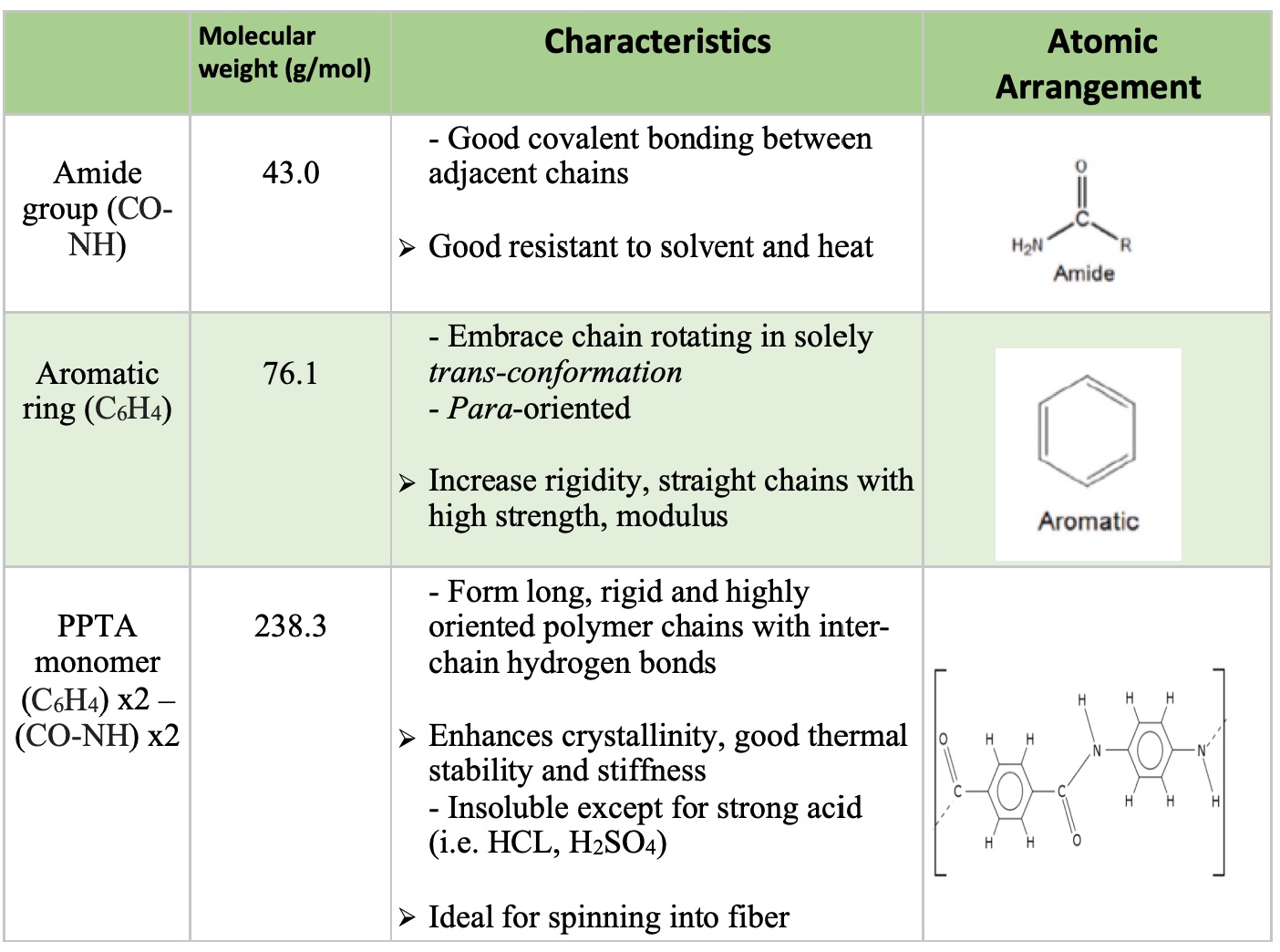

Aramid Fiber Composition

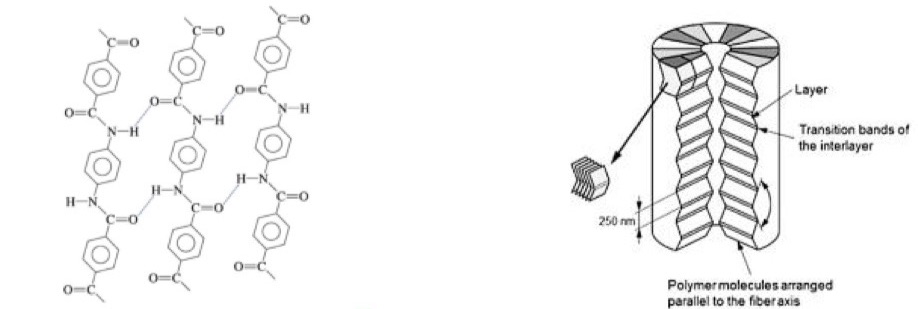

Atomic Arrangement

Aramid Fiber is a composition defined as poly para-phenylene terephthalamide (PPTA). Each PPTA monomer contains 14 carbon atoms, 2 nitrogen atoms, 2 oxygen atoms, and 10 hydrogen atoms in total of 28 atoms 10. That is, the molecular structure has two aromatic rings() and two amide groups(CO-NH) join at carbon 1 and 4 (para oriented) 11 12(See Table 2).

Table 2: Chemical composition & Atomic arrangement of Kevlar® Aramid Fiber13.

Table 2: Chemical composition & Atomic arrangement of Kevlar® Aramid Fiber13.

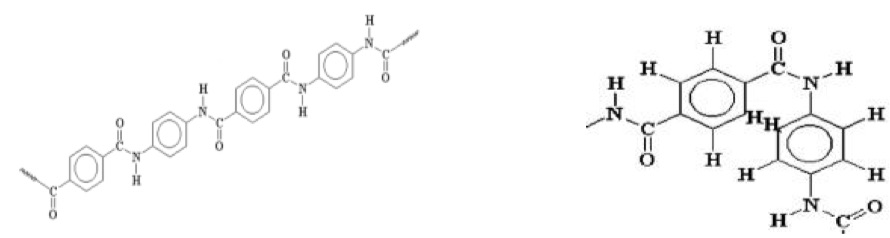

Conformational Isomerism

In trans-conformation, where the hydrocarbon groups are in the opposite side of the amide bond, causes the chain stretched out in an extremely straight manner and binds with other similar chains 14.

On the other hand, in cis-conformation, hydrocarbon groups are in the same side of the amide bond, the conformation hardly occurs because the aromatic rings hinder the molecule motion which prevent the chains from rotating and twisting around to conform.

Trans-conformation (Left) and Hindrance in cis-conformation (Right) 15

Trans-conformation (Left) and Hindrance in cis-conformation (Right) 15

As a result, PPTA conformation occurs almost entirely in trans-conformation forming a radial orientation which is the primary factor to make strong, stiff fiber since it long, straight and fully extended chains pack perfectly fit into the crystalline form.

Moreover, the high degree of chain alignment combined with hydrogen bonded amide increase the dispersion forces from stacking interaction between adjacent sheets, thus strengthening further resistance capacity as well as the thermal stability.

Microstructure

At least 85% of the amide groups enable the chain attaches directly to two aromatic rings 16 via covalent bonding between CO and NH groups. On inter-chain level, the amide group exhibits hydrogen bonding to bind adjacent chains together which forming a plat sheet and stacked upon each other as described in pleat structure in the longitudinal direction of fiber axis.

Hydrogen bonded sheet by cross-linking (Left) and Pleat Structure (Right).

Hydrogen bonded sheet by cross-linking (Left) and Pleat Structure (Right).

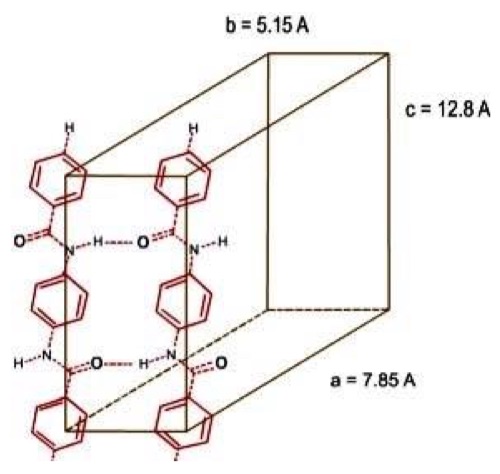

Crystal Structure

In the solute stages (Dope preparation), dopes exhibit liquid-crystalline properties since it has liquid crystal regions 17. The crystalline regions have the structure of monoclinic with pseudo-orthorhombic symmetry 18 19 20 which indicates three unequal axes (a ≠ b ≠ c) at right angle (𝛼 = 𝛽 = γ = 90 °) . Furthermore, the three lattice parameters in the unit cell measured at a: b: c = 0.787:0.519:1.29 nm.

Crystal structure in solution

Crystal structure in solution

The alignment of PPTA is defined by the angle between the amide group and the fiber axis (c-axis) which indicates the mis-orientation of chains with respect to fiber axis and has value of 12 °± 0.2 , . Thus, this angle contributes to predict the crystallinity and modulus of a fiber and can be treated for improvement. More on Defects and Strengthening mechanism.

Defects & Strengthening Mechanism

What make PPTA stands out is not only its intrinsic characteristics but also the way it was treated in post-solute process.

Point defect

Isolated Chain Ends

The chain-end defect occurs with mostly at end groups like –COOH, –NH 2 and its distribution are directly affecting deformation, failure process and the strength of PPTA 21. That is because the water in presence of creates PPTA chain scission by hydrolysis 22 in the solidification process of solution. Also, the treatment to control the defect is using 100% concentration as proposed in Manufacture Process - Step 3.

Interstitial

The swelling induced by the hydration of Sodium Sulfate () creates interstitial defects. The treatment to control the defect is further dissolute the by prolong the exposure time of fiber to boiling water as proposed in Manufacture Process - Step 7.

Material Treatment

Surface Heating

The Young’s modulus determines the extensibility of fiber when deform elastically and partially depends on the molecular orientation angle 23 24 which can be improved with post-treatment. The heat treatment solely focusing on treating the mis-orientation of PPTA chains with respect to fiber axis and results in a reduction from 12° to about 9°.

Consequently, the increase in total orientation results in increment of the fiber Young’s modulus, hence the elastic deformation ability and the chain linearity which essentially are the determinant of the tensile strength and are the two most important specifications of aramid fiber. More in Manufacture Process - Step 9.

Introduce Epoxy resin matrix

An adhesive Epoxy resin (E.g. Epon 828) was chosen for joining Kevlar fibers together, increase the attraction force, stiffness and thus strengthening the composite 25. Specifically, the resin through cross-linking reaction binds the PPTA filaments together and then changes state from a liquid to a solid.

Also, the process of introduce Kevlar into Epoxy resin matrix is via the exothermic reaction which indicates releasing heat involvement and since Epoxy is a thermosetting resin, it will remain formed and cannot be reversed afterwards. More in Manufacture Process - Step 5.

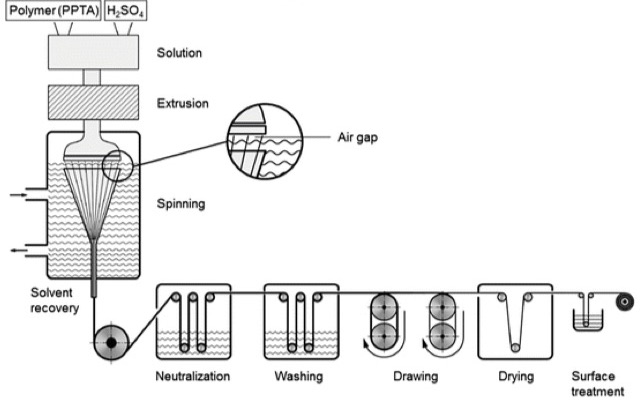

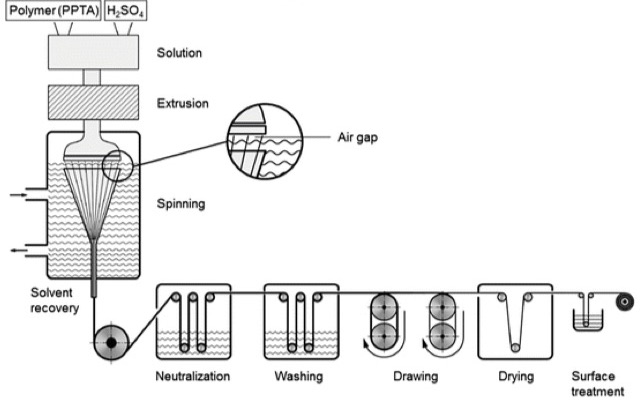

Manufacturing Process

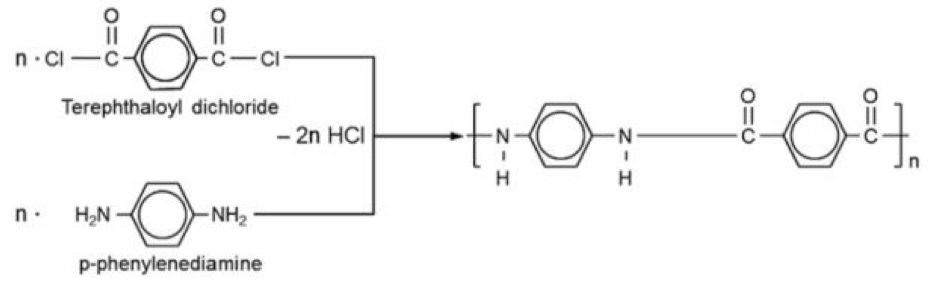

Polymer Synthesis 26 27 28

PPTA synthesis process consists of solid state polymerization under dry nitrogen conditions at low temperature in range of 10° - 20° C with N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone (NMP) as the solvent and calcium chloride (CaCl 2 ) as the ionic component

- Step 1: The condensation reaction of para-phenylenediamine PPD () and terephthaloyl chloride TCL () yielding hydrochloric acid (HCL) as a byproduct and results in monomer units.

Solution Polymerization of

Solution Polymerization of

- Step 2: The resulting PPTA polymers then neutralized with dilute Sodium Hydroxide (NaOH) in order to remove Hydrochloride acid (HCL) formed during the process.

At this stage, PPTA chains reportedly has average molecular weight of approx. 48350 g/mol 29 which means it has the polymerization degree of approx. 240 (i.e. has ≈ 240 units in total).

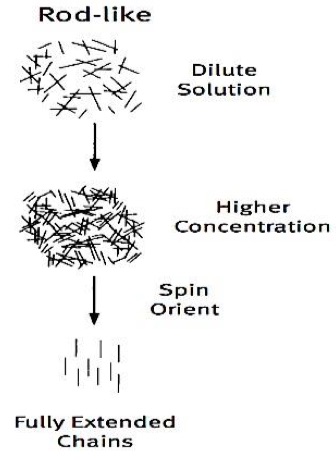

The PPTA chain is fully extended and consists of an alternation of rigid aromatic and amide groups in rod-like form as thermoset plastic with cross-linking and branched chains.

Chain behavior at different stages

Chain behavior at different stages

In addition, the behavior changes as PPTA dissolved in higher concentration during the Dope Preparation and consists of short range order with long range order in small volume (typical behavior of Liquid Crystalline as discussed earlier). Alternately spun into fully extended chains in Spinning Process.

Dope Preparation

In order to prepare liquid crystal dopes for the spinning process:

-

Step 3: Synthesized PPTA is dissolved in 100% concentration Sulfuric Acid () in order to achieve low viscosities and anisotropic feature of the spinning solution.

-

Step 4: The dopes that will be used to spin into fibers are melt above the melting point of 80° C.

Spinning Process

The spinning process of PPTA fibers, dry jet-wet spinning, give higher strength, a higher modulus but a lower elongation 30:

-

Step 5: The PPTA fibers are extruded in the form of liquid-crystalline dopes at about 85°C via a spinneret at 0.1-6m/s through the spinning nozzle and an air gap about 5mm between spinneret face inside a 1°C Water Coagulation Bath

-

Step 6: The spun yarns then pulled down by the downward stream of the spinning bath at rate of 100-200 m/min

Schematic Production of Aramid Fiber 31.

Schematic Production of Aramid Fiber 31.

-

Step 7: The recovered yarns then neutralized with Sodium Hydroxide (NaOH) again and subsequently washing out the water-soluble Sodium Sulfate () with boiling water to remove the introduced _interstitial defects.

-

Step 8: The yarns were draw and dried under tension on roller at the temperature range of 65-130°C at which stage it is the equivalent yarn to Kevlar 29 yarn for ballistic application based on DuPont™ manufacturing

-

Step 9: The surface treatment by apply temperature in range of 250 to 550 °C under 5-50% tension for time less than 10 minutes.

Epoxy Fabrication 32

The Aramid/epoxy composites consists of these processes:

-

Step 10: PPTA filaments passed through a mixed solution of diglycidyl-type resin (Epon 828) and 4,4’-diaminodiphenylmethane (DDM) with acetone at a 4:1:4.8 weight ratio.

-

Step 11: The treated fabrics are then dried at 25°C for 30 minutes and then at 70°C for 20 minutes.

-

Step 12: The fiber-reinforced epoxy composites are then cured under ambient conditions for 2 hours at 80°C followed by 2 hours at 150°C at a pressure of 150 psi under heating rate of 3°C/min.

-

Step 13: The molding cavity is then cooled to room temperature and releasing the pressure.

Testing & Quality Control

According to the primary manufacturer (DuPont™) of Kevlar, the ballistic testing standard for specified soft-body armor is the NIJ standard of the US DOJ. That is, the armor should be tough enough to withstand rounds fired of different types of bullets ranging from 9mm to .44 Magnums (Type II as mentioned in Requirements for soft-body armor).

Specifically, by using a destructive test and measure the indentation depth which is defined as Backface signature (BFS), the NIJ has conducted that that the soft-body armor Kevlar 956 33 (Kevlar 2934) protects against 35 36:

-

9 mm Full Metal Jacketed Round Nose (FMJ RN) bullets, with nominal masses of 8.0 g impacting at a minimum velocity of 358 m/s

-

357 Magnum Jacketed Soft Point (JSP) bullets, with nominal masses of 10.2 g impacting at a minimum velocity of 427 m/s

Environmental Impact

- Impact

Aramid Fiber is technically still a thermoset polymer which is very hard to deal when it comes to disposable. Since it does not melt but decompose at a very high temperature, it creates both human health and environmental health hazard whether its cancerous radiation or toxic gases. Other infamous solutions are burying either under mainland which leaking chemicals into ground water or create plastic island in the ocean which then eaten by sea creature and ultimately taken by human afterwards.

- Proposed solution

Recycle: As mentioned, this is not the primary solution because there is still no definitive solution to recycle Kevlar or even plastic.

Reuse: One way to reuse the body-armor is through thermal degradation in which include the process of pyrolysis and then separate the fiber and resin composite by mechanical washing machine37.

The method resulted yarns show 80% decrease in impact resistance, despite that, it still can be managed to reuse in other sectors such as research or teaching purposes.

Processing: Plastic-eating microbes are only on research scale but it has showed promising for plastic disposal.

However, as the bacteria grow stronger, it would require a better immune system to prevent undesired evolution which could end up potentially lethal for human.

- Future Plan

Improvement: Embedding a network of cross-linking carbon nanotubes (CNTs) to decrease the thickness and increase twice the strength of Kevlar 38.

Concern: The main concern for soft-body armor of researchers is further improving the physical properties of Kevlar fiber through the manufacturing process to maximize the adequacy for special parts like armpit, groin protection.

Disclaimer

This article offers knowledge and personal opinion based on the author’s point of view which perceived at the time of writing this article.

It is intended to serve “as-is” without any guarantee to work, proceed with caution. Your inputs and feedbacks are welcome as always.

-

B. A. Cheeseman and T. A. Bogetti, “Ballistic impact into fabric and compliant composite laminates,” Composite structures, vol. 61, no. 1, pp. 161-173, 2003. ↩

-

A. K. Dwivedi, M. W. Dalzell, S. A. Fossey, K. A. Slusarski, L. R. Long, and E. D. Wetzel, “Low velocity ballistic behavior of continuous filament knit aramid,” International Journal of Impact Engineering, vol. 96, pp. 23-34, 2016/10/01/ 2016. ↩

-

M. B. Mukasey, J. L. Sedgwick, and D. W. Hagy, “Ballistic Resistance of Body Armor

NIJ Standard-0101.06,” Regulation p. 3, July 08 2008. ↩

-

K. D. UK, “Kevlar Technical Guide Aramid Fiber,” ed: DuPont, pp. 1-4. ↩

-

MatWeb. (2017, June 12). MatWeb Material Property Data. ↩

-

K. K. Chang, “Aramid fibers,” Materials Park, OH: ASM International, 2001., pp. 41-45, 2001. ↩

-

G. Wypych, “PPTA poly(p-phenylene terephthalamide),” in Handbook of Polymers (Second Edition): ChemTec Publishing, 2016, pp. 542-545. ↩

-

F. Composites. (2014, June 12 ). Aramid Fiber. Available: http://www.aramid.eu/characteristics.html ↩

-

R. M. Byrnes Sr and A. Haas Jr, “Protective gloves and the like and a yarn with flexible core wrapped with aramid fiber,” ed: Google Patents, 1983. ↩

-

G. Wypych, “PPTA poly(p-phenylene terephthalamide),” in Handbook of Polymers (Second Edition): ChemTec Publishing, 2016, pp. 542-545. ↩

-

M. Jassal and S. Ghosh, “Aramid fibres-An overview,” pp. 296-299, 2002. ↩

-

B. S. Mercer, Molecular Dynamics Modeling of PPTA Crystals in Aramid Fibers. University of California, Berkeley, 2016. ↩

-

M. Jassal and S. Ghosh, “Aramid fibres-An overview,” pp. 296-299, 2002. ↩

-

M. Northolt, “X-ray diffraction study of poly (p-phenylene terephthalamide) fibres,” European Polymer Journal, vol. 10, no. 9, pp. 799-804, 1974. ↩

-

M. Northolt, “X-ray diffraction study of poly (p-phenylene terephthalamide) fibres,” European Polymer Journal, vol. 10, no. 9, pp. 799-804, 1974. ↩

-

M. Jassal and S. Ghosh, “Aramid fibres-An overview,” pp. 296-299, 2002. ↩

-

D. Ahmed, Z. Hongpeng, K. Haijuan, L. Jing, M. Yu, and Y. Muhuo, “Microstructural developments of poly (p-phenylene terephthalamide) fibers during heat treatment process: a review,” Materials Research, vol. 17, no. 5, pp. 1180-1200, 2014. ↩

-

M. Jassal and S. Ghosh, “Aramid fibres-An overview,” pp. 296-299, 2002. ↩

-

M. Northolt, “X-ray diffraction study of poly (p-phenylene terephthalamide) fibres,” European Polymer Journal, vol. 10, no. 9, pp. 799-804, 1974. ↩

-

M. Northolt and J. Van Aartsen, “On the crystal and molecular structure of poly‐(p‐phenylene terephthalamide),” Journal of Polymer Science Part C: Polymer Letters, vol. 11, no. 5, pp. 333-337, 1973. ↩

-

M. B. Mukasey, J. L. Sedgwick, and D. W. Hagy, “Ballistic Resistance of Body Armor” NIJ Standard-0101.06,” Regulation p. 3, July 08 2008. ↩

-

S. M. Lee, J. W. Sons, Ed. Handbook of Composite Reinforcement. 1992. ↩

-

D. Ahmed, Z. Hongpeng, K. Haijuan, L. Jing, M. Yu, and Y. Muhuo, “Microstructural developments of poly (p-phenylene terephthalamide) fibers during heat treatment process: a review,” Materials Research, vol. 17, no. 5, pp. 1180-1200, 2014. ↩

-

Y. Rao, A. Waddon, and R. Farris, “Structure–property relation in poly (p-phenylene terephthalamide)(PPTA) fibers,” Polymer, vol. 42, no. 13, pp. 5937-5946, 2001. ↩

-

C. S. S. S. R. WU, S. S. SHYU, “Kevlar Fiber-Epoxy Adhesion and Its Effect on Composite Mechanical and Fracture Properties by Plasma and Chemical Treatment.” Department of Chemical Engineering, National Central University, Chung-Li, Taiwan 320, Republic of China ↩

-

A. K. Dwivedi, M. W. Dalzell, S. A. Fossey, K. A. Slusarski, L. R. Long, and E. D. Wetzel, “Low velocity ballistic behavior of continuous filament knit aramid,” International Journal of Impact Engineering, vol. 96, pp. 23-34, 2016/10/01/ 2016. ↩

-

F. Composites. (2014, June 12 ). Aramid Fiber. Available: http://www.aramid.eu/characteristics.html ↩

-

Y. Rao, A. Waddon, and R. Farris, “Structure–property relation in poly (p-phenylene terephthalamide)(PPTA) fibers,” Polymer, vol. 42, no. 13, pp. 5937-5946, 2001. ↩

-

S. M. Lee, J. W. Sons, Ed. Handbook of Composite Reinforcement. 1992. ↩

-

D. Ahmed, Z. Hongpeng, K. Haijuan, L. Jing, M. Yu, and Y. Muhuo, “Microstructural developments of poly (p-phenylene terephthalamide) fibers during heat treatment process: a review,” Materials Research, vol. 17, no. 5, pp. 1180-1200, 2014. ↩

-

D. Ahmed, Z. Hongpeng, K. Haijuan, L. Jing, M. Yu, and Y. Muhuo, “Microstructural developments of poly (p-phenylene terephthalamide) fibers during heat treatment process: a review,” Materials Research, vol. 17, no. 5, pp. 1180-1200, 2014. ↩

-

C. S. S. S. R. WU, S. S. SHYU, “Kevlar Fiber-Epoxy Adhesion and Its Effect on Composite Mechanical and Fracture Properties by Plasma and Chemical Treatment.” Department of Chemical Engineering, National Central University, Chung-Li, Taiwan 320, Republic of China ↩

-

Named by the National Institute of Justice (NIJ) ↩

-

Named by the manufacturer DuPont™ ↩

-

K. D. UK, “Kevlar Technical Guide Aramid Fiber,” ed: DuPont, pp. 1-4. ↩

-

M. B. Mukasey, J. L. Sedgwick, and D. W. Hagy, “Ballistic Resistance of Body Armor” NIJ Standard-0101.06,” Regulation p. 3, July 08 2008. ↩

-

Í. V. S. e. S. Igor Dabkiewicz, Jossano Saldanha Marcuzzo, and R. d. C. M. S. Contini, “Study of Aramid Fiber/Polychloroprene Recycling Process by Thermal Degradation,” vol. Vol. 8 No.3, pp. 373-377, Jul - Sep. 2016. ↩

-

B. D. Ulery, L. S. Nair, and C. T. Laurencin, “Biomedical applications of biodegradable polymers,” Journal of polymer science Part B: polymer physics, vol. 49, no. 12, pp. 832-864, 2011. ↩